Book Review: “Æthelflæd: The Lady of the Mercians” by Tim Clarkson

Introduction

I recently read David Stoke’s novel on Æthelflæd, the daughter of the Anglo-Saxon king Alfred the Great and the Lady of the Mercians. Having enjoyed that, I desired to learn more and sought out Tim Clarkson’s biography: Æthelflæd: The Lady of the Mercians. Clarkson consolidates the sparse verifiable facts of Æthelflæd’s life and effectively presents a concise political history of Anglo-Saxon England between c. 500-1000 CE.

Synopsis & Historical Context*

In Æthelflæd: The Lady of the Mercians, Clarkson presents a chronological telling of Æthelflæd’s tale. He begins first with a balanced discussion of the sources documenting her life. Details mostly come from the various editions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. These include the pro-Æthelflæd Mercian Register, charters, and Irish and Welsh annals.

He also comments on the pro- and anti-Æthelflæd bents of these sources, highlighting potential biases which inform and color later discussions of her story. Recognizing biases is important for establishing as accurate and objective a picture of Æthelflæd’s life as possible.

Furthermore, the book summarizes aspects of Æthelflæd’s life. Topics covered include her marriage to Alfred’s ally Æthelred of Mercia, her relationship with her brother Edward, her various burh-building schemes, her military campaigns, and her piety.

*Please note some historical context is taken from the King Alfred’s Daughter book review linked in the introduction.

The Political Landscape

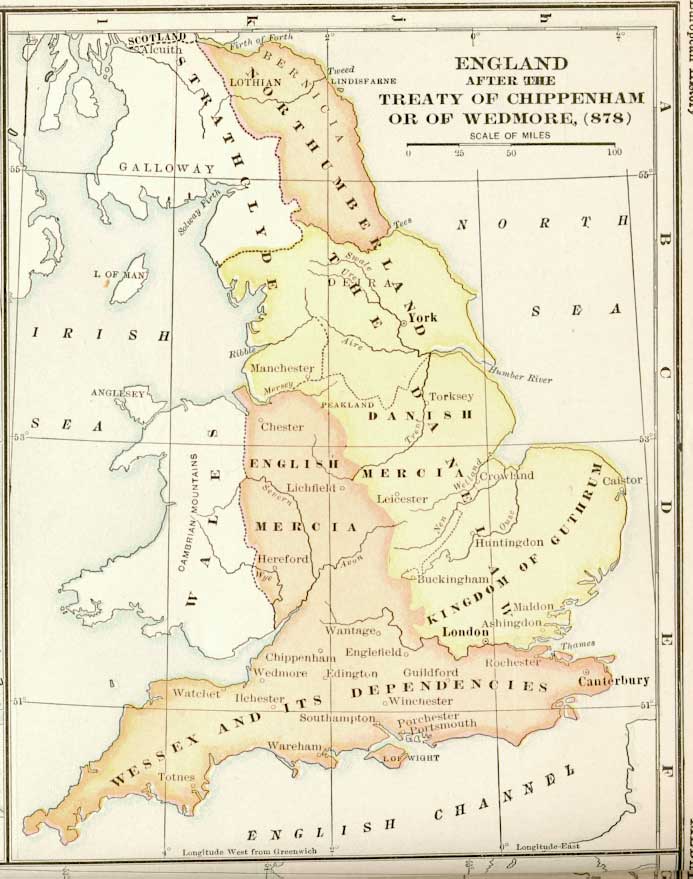

Æthelflæd lived during the ninth and tenth centuries, a formative time in English history. England as a unified country didn’t yet exist, but the once-disparate kingdoms slowly began to meld together. Anglo-Saxon England resembled something of a geographical patchwork quilt. The kingdoms of Wessex, Mercia, and Northumberland occupied the southern, central, and northern portions of England. Scotland harbored Picts to the far north, the Cornish thrived in the southwestern peninsula, and the Welsh were tucked to the west. The eastern part of Mercia fell under the control of the Danish, and this land became known as the Danelaw.

Martin J. Ryan, in Anglo-Saxon England, perhaps best summarizes the nature of Wessexian politics and unification under one ruler in the tenth-century:

“That a unified England would emerge over the course of the tenth century does not mean that such unity was inevitable nor that there had long existed the idea of or the desire for political unification, an England impatiently waiting to be born.” Ryan further expresses that West Saxon territorial expansion ebbed and flowed throughout the course of the tenth century, characterized by “shifting allegiances, temporary alliances and fluctuating levels of power and authority.”1

The Lord and Lady of the Mercians

Æthelflæd became known as “Lady of the Mercians” by virtue of her marriage to Æthelred, a Mercian nobleman with unknown familial origins. Alfred wed her to his comrade to shore up the alliance between Wessex and Mercia. Later, Æthelflæd and Æthelred had one daughter named Ælfwynn.

The true nature of the alliance between Wessex and Mercia, especially during Æthelflæd’s reign, remains up for debate. Was Mercia a kingdom and its rulers regarded as monarchs? Or was Mercia more subordinate to Alfred and later Edward the Elder? Some contend that Æthelred ruled as king in name and action, given that his status appears as rex (Latin for “king”) in both a version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and Irish sources.2

Regardless of the specific nuances of their rule, Mercia continued the Alfredian burh scheme (discussed below) and worked to restore its border to its full pre-Danelaw extent. Mercia alternated between periods of conflict and peace with the Danish Vikings as well as incursions from the Norse-Irish.3

Æthelflæd played a key role in ensuring the stability of her lands. Her efforts would later help unify the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms under one ruler.

Alfred the Great and His Reforms

So where does Alfred fit into all of this? And, how was he able to expand and maintain West Saxon holdings?

In an effort to consolidate his hold on his kingdom, Alfred exerted his control through both military reorganization and the building of burhs, or fortified settlements including both soldiers and civilians within an enclosed location.

The fyrd comprised, as Clarkson writes, “the armed retinues of noblemen who were obliged to bring their forces to supplement the royal warband.”4 This had long been the traditional method of war-mustering rather than a ruler having a standing army, as was common in later periods. Alfred shifted his fyrd into a more permanent force, able to more quickly fortify his burhs and embark on military campaigns. As a result, the campaigning season could feasibly follow a more ad hoc schedule rather than fall subject to seasonal considerations such as planting in spring and harvesting in the autumn.

In addition to the fyrd reorganization, Alfred’s construction of burhs allowed him to guard his lands. Under later kings such as Edward the Elder, the burhs also served as locations from which to launch campaigns aimed at territorial expansion. A tenth-century document known as the Burghal Hidage lists 33 burhs including Winchester, Exeter, Southampton, Bath, Malmesbury, Worcester, and Warwick. Some of these still survive to the present day.

Æthelflæd’s Military Campaigns

Clarkson also devotes a fair amount of time detailing Æthelflæd’s military campaigns. Her role as a warrior, especially in a time heavily dominated by patriarchal values, has fascinated chroniclers, scholars, and historians throughout the centuries.5 “While no tenth-century sources indicate that Æthelflæd ever personally engaged in combat,” Scott Thompson writes, “the warrior role has long been an essential feature of her story in the modern imagination.6

Throughout her life, Æthelflæd spent time contending with both domestic and foreign threats. Domestically, her cousin Æthelwold (the son of Alfred’s elder brother) claimed the throne upon the ascension of Æthelflæd’s brother Edward in 902 CE. His defeat and death at the Battle of the Holme solidified Edward’s reign.

Foreign incursions often came at the hands of Vikings, Norse-Irish, and Welsh. One particularly potent threat came from Ingimund, the leader of a group of Norse-Irish who entreated Æthelflæd for permission to settle on the Wirral peninsula. Clarkson notes they lived peacefully side-by-side for a time, and that the peninsula proved an ideal place to settle if that were truly Ingimund’s aim.7 Alas, this was not to be; Ingimund attacked the city of Chester, but Æthelflæd mustered a large group of forces and assisted Chester in repelling the threat.

The author discusses other battles and military campaigns at length, often commenting on source veracity and if events may or may not have transpired as detailed in the historical record.

Æthelflæd and Her Piety

Given the dearth of any records specifically written by Æthelflæd herself, it’s hard to surmise her opinions on religion. However, we can make educated guesses based on existing charters, annals, and other documentary sources. In Dying and Death in Later Anglo-Saxon England, Victoria Thompson writes that

“She[Æthelflæd] was extraordinary, in her ability to order the building of a minster-mausoleum, to fund intercessory masses and to translate saints’ relics, but ordinary in that her investment in these bones, buildings and ceremonies typified the behaviour of great laymen and women in the decades around 900…”

Victoria Thompson, Dying and Death in Later Anglo-Saxon England, vol. 4 (Boydell & Brewer, 2004: 8, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt81qrm.

Æthelflæd founded or endowed several churches, often constructing burhs centered around prominent religious locations. Conversely, the Lady of the Mercians sometimes built new churches or replaced existing ones in existing settlements as the burh developed. The princess also presided over the transfer of the bones of St. Oswald – an important Mercian saint – from Bardney Abbey in Lincolnshire to a new priory she established in Gloucester, one of her most prominent burhs. Upon their deaths, Æthelred and Æthelflæd were put to rest in St. Oswald’s Priory.

Taken together, Clarkson presents a picture of a highly intelligent noblewoman who sought to balance her Mercian and Wessexian interests, protect her people, and continue her father’s agenda of consolidating the Anglo-Saxon hold over England and contending with various Norse, Danish, and Irish incursions.

Review

Admittedly, telling Æthelflæd’s tale requires a lot of connecting the dots between fragmentary sources, inherent and explicit bias, archaeological evidence, and a modern lens in order to craft a balanced story. It’s easy to ascribe traditionally-male characteristics to Æthelflæd, as noted by Thompson in his book chapter in Feminist Approaches to Early Medieval English Studies. And yet, Clarkson does a remarkable job of allowing Æthelflæd to shine in her own way.

“As far as we know, Æthelflæd is the only woman [of the Viking Age] who exercised such power over a period of years rather than months. She accepted the role willingly, with all the responsibilities that went with it, discharging her duties effectively. Whatever challenges she had to face as a lone female in a political landscape dominated by men she plainly overcame them. Her achievements show beyond doubt that she was the right person at the right place at the right time…While it might be argued that we should be wary of describing as queen a woman who may have been content to be addressed as hlæfdige [lady], her achievements and her place in history make the regal title seem fitting”.

Tim Clarkson, Æthelflæd: Lady of the Mercians (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2018): Chapter 10.

More technically-speaking, Æthelflæd: The Lady of the Mercians takes on an academic bent, but is approachable in its prose style. Some might struggle with Clarkson’s explanations of the sources, political factions at play, and other historical contextualization, especially if one doesn’t have a lot of familiarity with the subjects at hand. On the other hand, Clarkson offers plenty of explanatory footnotes and citations for those interested in exploring further. He also masterfully tackles a complex and multifaceted historiography.

Overall, Æthelflæd: The Lady of the Mercians doesn’t, perhaps, reimagine Æthelflæd’s story in any new or earth-shattering way. Arguably, however, Clarkson presents a concise and well-balanced take on Æthelflæd with a focus on her military and political accomplishments against a backdrop of a tumultuous historical era.

Book Summary

Title: Æthelflæd: The Lady of the Mercians

Author: Tim Clarkson

Publisher: John Donald

Publication Year: 2018

Page Count: 325pp (Kindle eBook)

Featured image: King Alfred the Great riding a horse (Photos.com)

*This post contains an affiliate link to Bookshop.org, an organization which supports independent bookstores. If you purchase this book through Bookshop, I will earn a small commission that goes towards the running of this website. Please refer to my affiliate disclosure for more information.

- Martin J. Ryan, “Conquest, Reform, and the Making of England,” in The Anglo-Saxon World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013): 284-28, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt32bt51.11. ↩︎

- Ibid. , 87. ↩︎

- For more information, check out F.T. Wainwright’s 1948 article on Ingimund’s invasion (subscription may be required). ↩︎

- Tim Clarkson, Æthelflæd: Lady of the Mercians (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2018): 76. ↩︎

- Scott Thompson Smith, “Remembering the Lady of Mercia,” in Feminist Approaches to Early Medieval English Studies, edited by Robin Norris, Rebecca Stephenson, and Renée R. Trilling (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2023): 97, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv32dnb90.7. ↩︎

- Ibid., 97. ↩︎

- Clarkson, Æthelflæd, Chapter 5. ↩︎