Book Review: “Scourge of Henry VIII: The Life of Marie de Guise” by Melanie Clegg

Introduction

Amazon has a nasty habit of sending me push notifications about Kindle sales. I say nasty because it induces me to buy more books. Fortunately, ebooks take up less shelf space than physical books! On the other hand, I am ensuring my “to-read” list grows and grows in spades. On one of these occasions, I saw a book about the mother of Mary, Queen of Scots, the sister monarch to Queen Elizabeth I. Intriguingly titled Scourge of Henry VIII: The Life of Marie de Guise, I read the premise, and it sparked my interest.

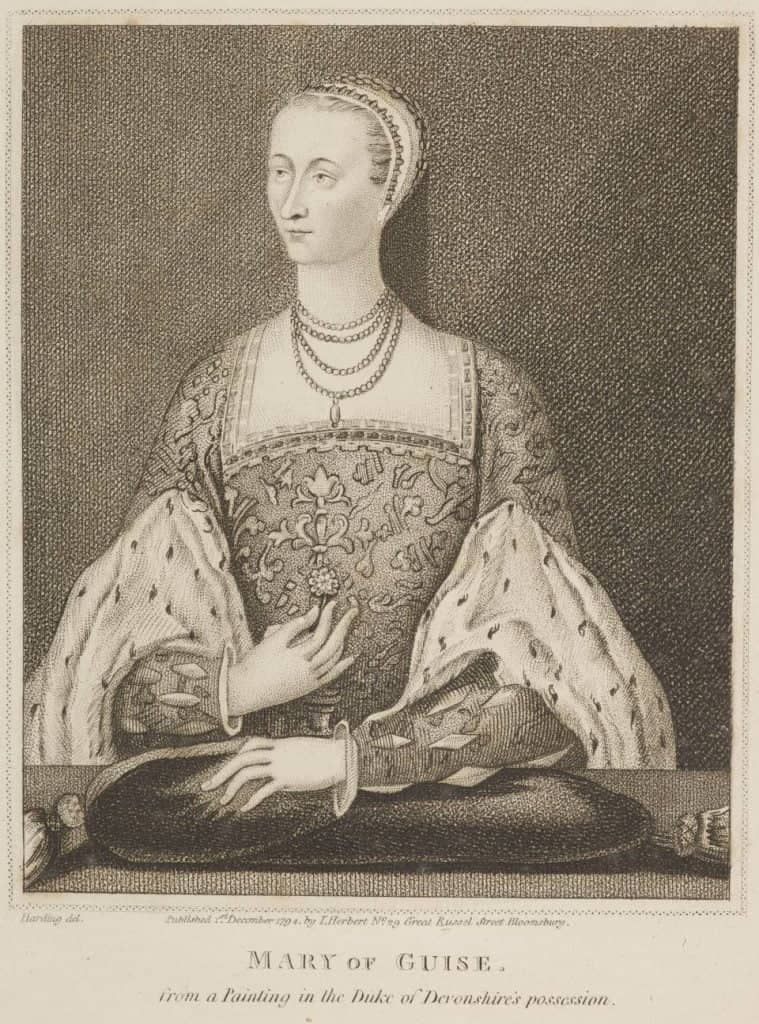

Mary, Queen of Scots continues to intrigue both historians and the general public—but the story of her mother, Marie de Guise, is much less well known. A political power in her own right, she was born into the powerful and ambitious Lorraine family, spending her formative years at the dazzling, licentious court of François I. Although briefly courted by Henry VIII, she instead married his nephew, James V of Scotland, in 1538.

James’s premature death four years later left their six-day-old daughter, Mary, as queen, and presented Marie with the formidable challenge of winning the support of the Scottish people and protecting her daughter’s threatened birthright. Content until now to remain in the background and play the part of the obedient wife, Marie spent the next eighteen years effectively governing Scotland—devoting her considerable intellect, courage, and energy to safeguarding her daughter’s inheritance by using a deft mixture of cunning, charm, determination, and tolerance. This biography, from the author of Marie Antoinette: An Intimate History, tells the story and offers a fresh assessment of this most fascinating and underappreciated of sixteenth-century female rulers.

From Amazon

After finishing some reading material on ancient Greece, I finally decided to pick up Scourge of Henry VIII.

Historical Context

Introduction to the World of Marie de Guise

The sixteenth century was a veritable hotbed of political intrigue. England, France, the Holy Roman Empire, and others vied for power and prominence in Western Europe. Alliances and treaties were signed with marriages and broken with wars. Men lived and died by their lord’s words. Women bore little power and found themselves yoked to the stringent social and gender mores of the age. It was into this world Mary of Guise (1515-1560) was born.

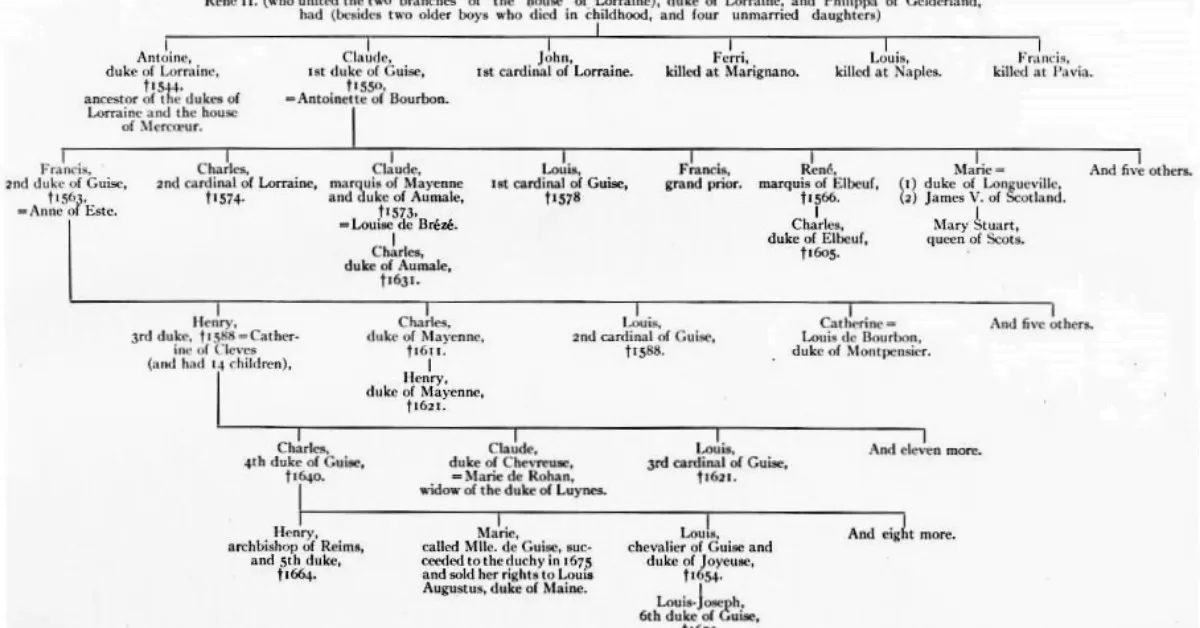

Marie, to use the French rendering of her name, was born into the powerful and illustrious Guise family. This house in itself was a cadet branch of the House of Lorraine. Close-knit, wealthy, and ambitious, the Guises dominated the French court during the reigns of Francis I, Henri II, and their successors. Their close alliance with French royalty yielded many benefits including dukedoms, papal positions, and, eventually, marriage into the family itself.

According to Stuart Carroll, author of Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe,

The Guise rise to power was initially predicated on royal service and the favor of the King of France. But their ability to profit from it in the long term, and to hold on to power once favour was withdrawn, was due to an extraordinary level of family solidarity.1Stuart Carroll, Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe (United Kingdom: OUP Oxford, 2011): 22.

The family’s meteoric ascension began with Marie’s father, Claude de Lorraine (1496-1550).

The Rise of the House de Guise

Claude’s rise to power involved both an advantageous marriage and currying favor with the French monarch. At the age of 17, Claude married Antoinette, a daughter of the illustrious House of Bourbon, another powerful French noble family. They produced several children including, among others:

- Marie (1515-1560), who first married Louis II, Duke of Longueville, and second, King James V of Scotland

- Francis, Duke of Guise (1520-1542)

- Charles of Guise, Duke of Chevreuse, Archbishop of Reims, and Cardinal de Lorraine (1524-1574)

- Claude, Duke of Aumale (1526-1573)

- Louis, Cardinal de Guise (1527-1578)

Cementing himself with such a powerful family ensured that Claude and his children possessed the connections needed to advance themselves. The first prestigious honor bestowed on the family was the right to form a cadet branch of the House of Lorraine by the granting of a dukedom.

Claude became the titular Duke de Guise when

Francis the First, King of France…erected the County of Guise into a Dukedom and Peerdom, in favour of Claudius of Lorrain, in the year 1527.2Jacques-Auguste de Thou, et al., The True history of the Duke of Guise extracted out of Thaunus, Mezeray, Mr. Aubeny’s Memoirs and the Journal of the reign of Henry the Third of France (London: R. Baldwin, 1683).

From there, the Guise fortunes continued their ascent.

The Auld Alliance

At the Beginning

Historically speaking, the relationship between England and its fierce Scottish and French neighbors resembled the ever-churning tempestuous waters of the English Channel. Therefore, in an “enemy of my enemy is my friend” manner, France and Scotland formed a partnership that is colloquially called the “Auld Alliance”.

In the medieval period, England claimed many holdings in France, in part due to the Norman conquest in 1066. Subsequent English monarchs held fiefdoms in France as part of their inheritance. French queens such as Eleanor of Aquitaine, wife of King Henry II, and Isabella de Angoulême, wife of King John, added territories that formed a key point of contention between these two countries. Later kings would attempt to assume the French throne in their own rights. Ultimately, though, England would cede their claim with the loss of Calais under Mary I in 1558.

The complicated nature of alliances did not end with royalty. Many noblemen throughout medieval and early modern history held lands in Scotland, England, and/or France. As a result, kin-based relationships between these three countries prevailed.3M.A. Pollock, Scotland, England and France After the Loss of Normandy 1204-1296 (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer, 2015): 6.

The passing of Normandy back into French control in 1204 marked a turning point in Anglo-Franco-Scottish relations, especially in terms of correspondence.

…[O]fficial correspondence between the French and Scottish crowns occurred more frequently as a reaction to political developments in England. Families whose lordships were primarily in England were increasingly forced to flee to France because of problems they faced with the English king…These families perpetuated cross-[English] Channel alliances engineered against the English crown.4Ibid., 6.

Causes for a New Alliance

The later part of the thirteenth century, however, saw a marked decrease in communication between Scotland and France. Marital unions and little else bonded the two countries. The loss of Normandy slowly eroded the holding of lands in multiple kingdoms. Consequently, those kinship ties so important to cross-Channel affinities declined as people became more vested in happenings within their own borders than without. Additionally, many lord renounced their holdings and sought refuge in one country rather than spending time between two or three. Thus developed the tentative foundations of a national identity.

Still, it became apparent to both France and Scotland that a renewed alliance was in their best interest. English incursions into Scottish and French territories and other political happenings necessitated discussions and negotiations.

For instance, King Edward I of England, at the behest of the Scots, arbitrated and decided the Scottish succession with the heir to the throne being a tiny maid. Despite his reputation as a just man, the nature of England’s relationship with Scotland superseded his role as an impartial judge. English monarchs desired Scotland’s fealty, but, as could be expected, Scotland preferred its independence. Presiding over the Scots succession crisis enabled Edward to marry the Scots heir, Margaret the “Maid of Norway”, to his son in 1289, thus potentially bringing Scotland to heel.

The threat of England’s power precipitated the need for an agreement between Scotland and France to check England’s influence.

The Heralding of a New Alliance

In 1295, France and Scotland solidified their alliance with an official treaty. Between England encroaching on Scottish territory and renouncing its fealty to the French king, this alliance represented the best chance for these two countries to stand against the English tide. The ‘Auld Alliance’ held true until the sixteenth century. In 1560, England and Scotland signed the Treaty of Edinburgh, replacing the Franco-Scottish alliance with an English one. However, the Auld Alliance formed a key component of Scottish nationalism, one that still resonated well into the life of Marie de Guise.

Review

Introduction to “The Life of Marie de Guise”

Writing history for popular consumption presents an interesting conundrum: how can one distill historical information in an engaging manner without compromising the integrity of the facts? It’s tricky, especially if one thinks uncritically about their subject. That is, they hold an uncompromising bias towards their person or persons.

As someone who enjoys reading popular historical fiction and non-fiction both, I have noticed this with many authors. It’s easy to get caught up in writing about a topic you’re passionate about. However, this passion sometimes comes at the price of one-sided storytelling. Everything they do is great. Or they’re fantastic because they accomplished this when no one else did. Or they never did anything bad.

The beauty of history comes from its openness to interpretation. This is a personal preference, but I enjoy a balanced approach to history writing, both the ups and the downs. Melanie Clegg’s clear bias towards Marie de Guise abounds in her book. I can’t fault her for her passion. However, it sometimes made for a less-than-enjoyable reading experience.

Sources

The bread-and-butter of any historical book comes from its sources. Primary and secondary sources give life to history. Writing on history requires the use of sources to present arguments and information, and, in many cases, to give readers a sense of a time different than our own.

Clegg pulls in a variety of excellent sources from Marie’s personal letters to scholarly and popular secondary sources. However, she fails to pull them together into a cohesive bibliography. Rather than organizing them by primary and secondary, as most historians are apt to do, Clegg throws them willy-nilly into a mess of a list. Anyone interested in investigating research further after reading her book must slough through this mess as thick as the fog over a Scottish loch.

One source I would like to highlight as what promises to be an excellent resource on the Guise family is Stuart Carroll’s Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe. I skimmed through it as I was researching historical context, and the bits and bobs I read impressed me. It will most likely make my never-ending to-read list.

Also worth noting are Marie’s personal letters. Marie’s persistent love and loyalty to her family comes through as one of the persistent themes presented in Clegg’s work. I proved initially skeptical at this until I started perusing the letters. Clegg hits the proverbial nail on the head in enlightening readers on Marie’s family dynamics, something rare when one reads about prominent Renaissance noble families.

What About Henry VIII and Marie de Guise?

Perhaps one of the sharpest criticisms I have of The Life of Marie de Guise comes from the title itself. The first part reads Scourge of Henry VIII. One might think the larger-than-life, infamous English monarch (learn more about him in this mini-bio) would play a more significant role in Clegg’s book than he actually does. Other than cursory mentions where the author portrays him as a boorish, bumbling, tyrannical foil to the vivacious, intelligent Marie de Guise, the narrative relegates him to the sidelines.

Marie does not come off as a scourge to Henry Tudor in this biography. The term ‘scourge’ insinuates that she was constantly a thorn in his side, threatening his very existence. Had this been the case, Clegg should have made that argument a key thesis in her book. In this, alas, she failed.

Should You Read This Book?

Author Melanie Clegg crafts a respectable biography of Marie de Guise, a remarkable woman who controlled her own life in early modern Europe, a time in which women had precious few opportunities for independence. Marie successfully navigated the luscious but dangerous courts of Scotland, England, and France. She married a king and mothered a queen. She was an exemplary member of one of the most prominent noble families of the Renaissance. In short, Marie de Guise is a woman well worth studying.

Should you read this book? My answer is that it depends on who is reading it. General readers will most likely find this to be a fascinating first foray into learning about Marie de Guise, especially if one is not familiar with her. Scholars looking to use this for historiographical purposes or looking to tap into Clegg’s research would do well to look elsewhere.

First and foremost, The Life of Marie de Guise presents itself as a popular historical biography. Its focus centers on presenting information in a clear, concise, engaging manner over presenting a historical argument. I would not recommend it as adding something new and spectacular to the study of this astonishing lady in terms of historical scholarship. However, it’s worth a read as a foundation for further, more pointed research.

Book Summary

Title: Scourge of Henry VIII: The Life of Marie de Guise

Author: Melanie Clegg

Publisher: Pen and Sword History

Publication Year: 2016; published online in 2019

Page Count: 224pp

Sources

- Carroll, Stuart. Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe. United Kingdom: OUP Oxford, 2011.

- de Thou, Jacques-Auguste et al., The True history of the Duke of Guise extracted out of Thaunus, Mezeray, Mr. Aubeny’s Memoirs and the Journal of the reign of Henry the Third of France. London: R. Baldwin, 1683.

- Pollock, M.A. Scotland, England and France After the Loss of Normandy 1204-1296. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer, 2015.